The Endangered Post Up

A species can become endangered when it lacks the ability to adapt to a changing environment. The problem is compounded when another species is introduced that has a competitive advantage in the new habitat.

There was George Mikan before Wilt and Russell’s rivalry. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is the NBA’s all-time leading scorer. More recently, Hakeem Olajuwon was twice the Finals MVP as he led Houston to back-to-back championships. Shaq, a 15-time all-star, won championships in Miami and L.A., four in total, during his hall-of-fame career.

For decades, there have been great NBA teams that relied on the inside offensive presence of a center. It’s why NBA teams have prioritized drafting big. Allen Iverson broke the mold when, as a PG, he was drafted 1st overall in 1996. The 1st-overall pick was supposed to look like Ralph Sampson, Olajuwon, Patrick Ewing, Brad Daugherty, or David Robinson (the 1st overall picks from 1983 to 1987). And if not that, then Chris Webber or Larry Johnson. In a sport where the objective is to put a ball through a hoop that sits 10 feet off the ground, size is supposed to be a huge advantage (both on offense and on defense).

So, why does it seem like any footage of great post-up bigs is in standard definition? Why are recent 1st-overall picks more commonly perimeter players like John Wall, Kyrie Irving, Derrick Rose, or Markelle Fultz? How is it that some of today’s best lineups don’t have a player taller than 6’9”? When did feeding the post go from the bread and butter of so many great teams to a non-factor? This season, the Atlanta Hawks are averaging less than 1 post-up FGA per game!

The Post-Up Offense And Players Who Rely On It Are Endangered.

This season, NBA teams are averaging just about 5 FGA from post ups a game. If we include post ups that lead to free-throws or turnovers, teams are averaging 7 post up possessions per game. Shaq alone probably averaged more post ups in a half, and Wilt probably averaged more in a quarter.

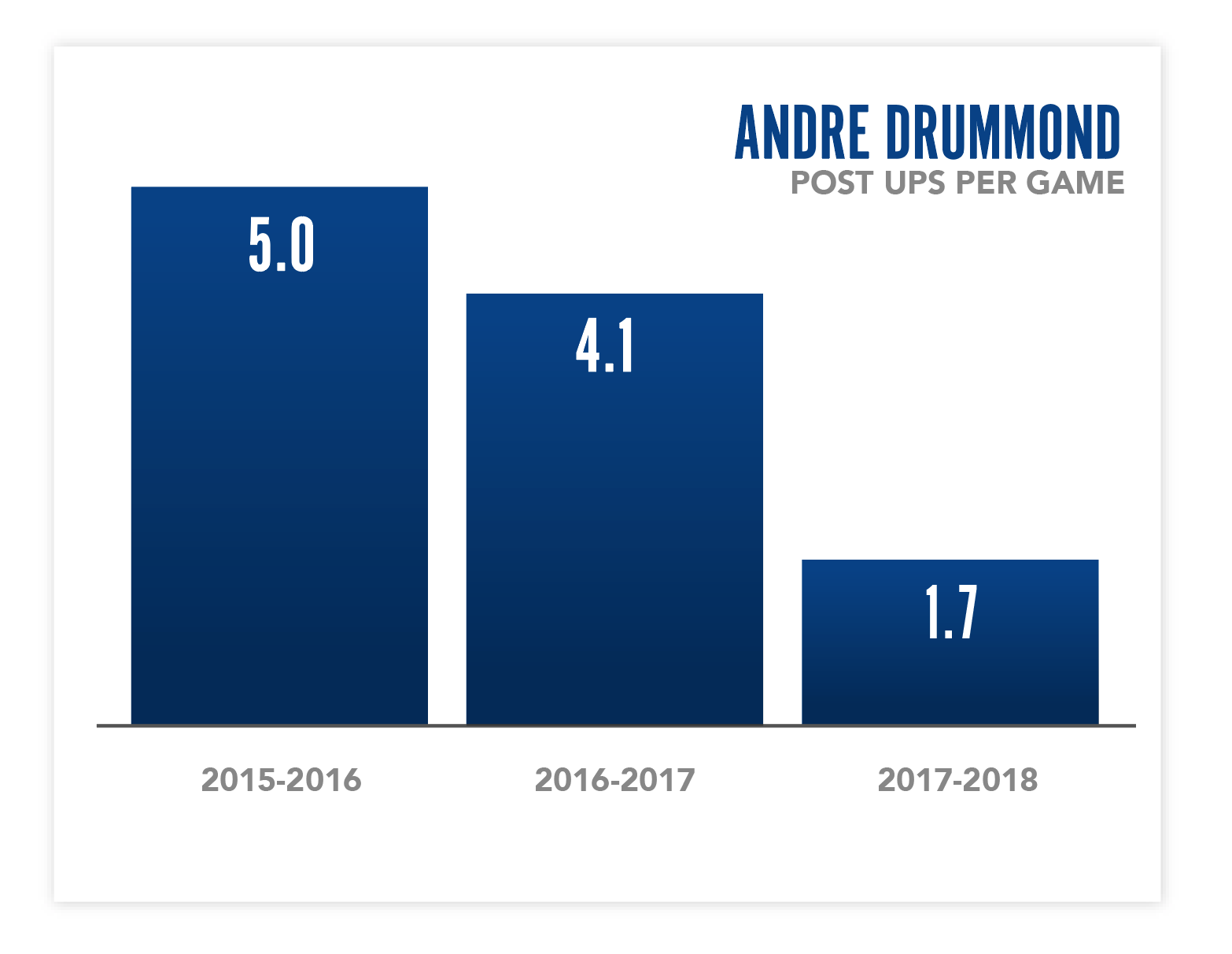

Some might argue that teams post up less because it’s a lost art; today’s bigs don’t have the fundamentals and touch around the hoop. No, the issue isn’t with the players. Coaches are scheming to post less. What else would explain how Andre Drummond’s post ups have decreased over the last three seasons as he enters his prime as a player?

There are three reasons NBA teams are abandoning the post up. It’s an inefficient shot, it clogs the paint and inhibits drives and cuts, and the players that are typically best at posting up struggle to meet the defensive demands for a center in the modern NBA.

Analytics has changed how we view basketball. We now have the numbers that tell us when our intuition misses the mark. Post ups, like mid-range jumpers, always felt like good offense. At lower levels—like high school, college and AAU, where there exist great mismatches in size and players aren’t typically as efficient from 3—they were and still are. Since players and coaches begin their careers and form foundational views on the game at these lower levels, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that so many expect the same principles that apply to the amateur game to extend to the pro ranks. They don’t.

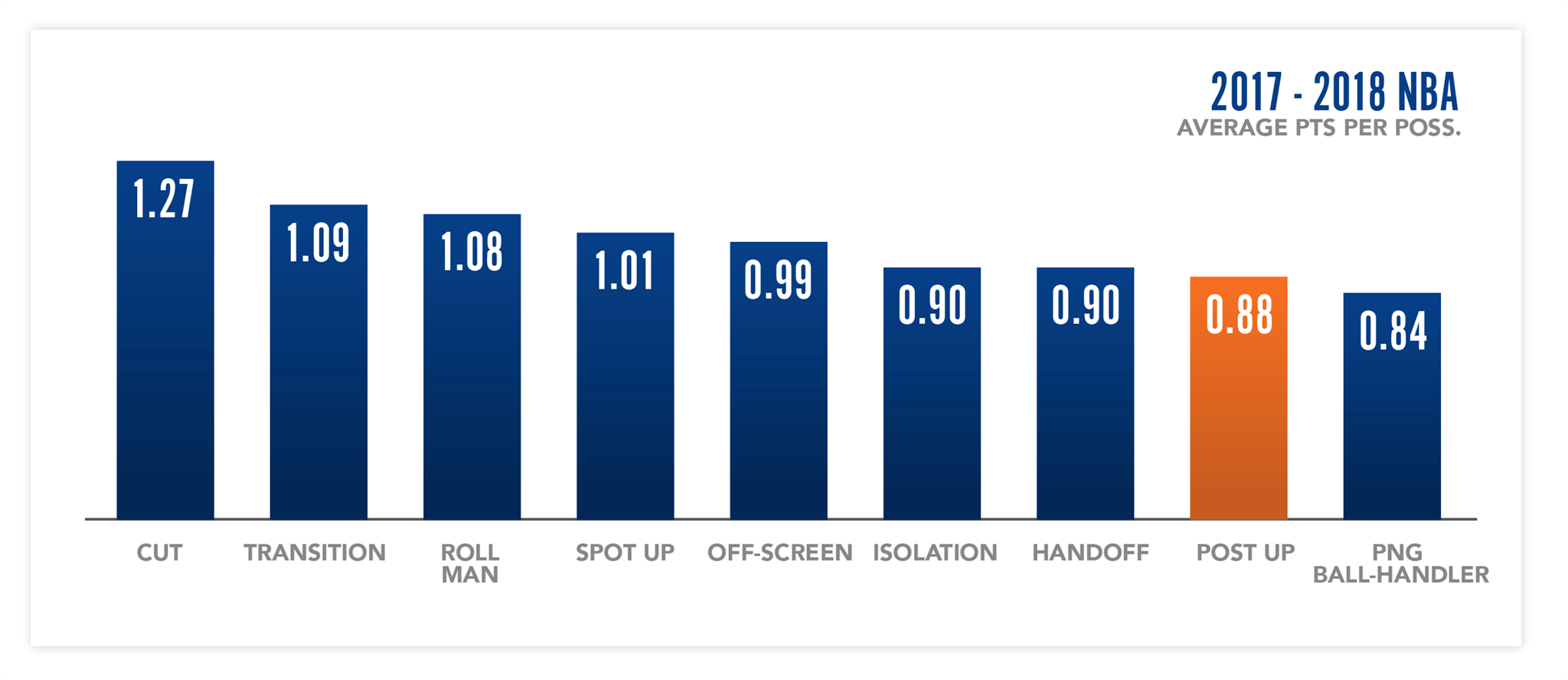

Thanks to more-advanced data-gathering efforts in recent years, we now know how efficient players and teams are when attempting certain fundamental basketball actions. The chart below shows that the post up is one of the least efficient offensive play types. It’s significantly less efficient than a player spotting up for a jumper or a player rolling or cutting to the hoop.

Boston guard Marcus Smart gets a lot of criticism for taking 4.6 3-pointers a game when he’s only shooting 29.9%. The attacks are justified. That’s not a good 3-point percentage. But is anyone criticizing Dwight Howard for averaging 6.5 post ups per game, or Marc Gasol for averaging 5.5?

This season, NBA teams are averaging 0.88 points per post up. That’s the equivalent of shooting 29% from 3. In other words, the average post up is worse than a Marcus Smart 3-point attempt.

Dwight Howard and Marc Gasol are both averaging about 0.78 points per post up. That’s the equivalent of shooting 26% from 3. This season, 181 players have taken at least 100 3-point attempts. They’ve all made at least 26% of them. 171 of the 181 are shooting better than 30%.

Here’s another way to look at it. Teams get about 100 possessions a game. Suppose one team used those possessions on the equivalent of a Dwight Howard post-up and their opponent used them on a Nikola Mirotic 3. The Mirotic team would win in a rout, 125-78.

No team in the NBA is averaging more than 0.98 points per possession on post ups. That’s the equivalent of shooting 33% from 3. The league average 3-point percentage is 36%.

Everyone’s Trying To Win The Space Race

Post ups also inhibit spacing. When a big is stationed on the block, his defender will be there too. That puts two big bodies exactly where the team’s wings want to drive or cut. When teams space appropriately, cuts to the hoop can be particularly efficient. The Warriors lead the league in cuts by a good margin and average 1.30 points per cut. Every team in the NBA averages at least 1.15 points per cut, which means cuts from the worst cutting team are still significantly more efficient than post ups from the league’s best post-up team.

If an offense is going to consistently send their big to the block, then the opposition knows they have their big rim protector, whether it’s Rudy Gobert, DeAndre Jordan or Hassan Whiteside, around the hoop to clean up on drives. With less to worry about if they get beat, the perimeter defenders can guard the 3 more aggressively.

As recently as 2013-14, teams were still employing offenses that allowed the Indiana Pacers to do exactly this. Roy Hibbert roamed the paint while wings like Lance Stephenson and Paul George took away the perimeter options. In that season and the one prior, Indiana was the only team to allow fewer than 1 point per possession on average.

But, if a team can field five players that can shoot from the perimeter, opposing rim protectors can no longer wait in the paint. They have to challenge 3-point attempts, and if the opposition is screening effectively, they might have to switch onto a smaller and quicker player on the perimeter.

Defending the Arc

This leads to the third reason teams are abandoning the post up. As offenses rely more on perimeter offense and the 3-point shot in particular, defenses need to be better prepared to defend that offense. The changes have greatly impacted the defensive expectations of NBA centers. Today’s centers need to cover the entirety of the halfcourt, not just the space around the hoop. When you can’t give Steph Curry or James Harden an inch of space off a screen, centers need to be able to switch onto guards and at least momentarily discourage the 3-point attempt. The same wide-bottomed bigs that can throw their weight around on the block on offense are typically too slow to chase guards on the perimeter.

The NBA center’s habitat has evolved. The game is faster and more perimeter-oriented, and those that don’t have the skills to adapt aren’t surviving.

After shooting 55% from the floor in the regular season in 2016-17, Oklahoma City’s Enes Kanter could only get on the court for 9 minutes a game in the playoffs. After a dominant freshman season at Duke, Jahlil Okafor was drafted 3rd overall 2015 by the Philadelphia 76ers. A couple years later, he was dumped off to Brooklyn, and many wonder if he’ll ever be more than an end-of-the-bench guy. In the 2017 offseason, once-coveted big-man Dwight Howard could’ve been had for a six-pack. All of the above would be highly valued commodities in the 90s.

Today’s best center might be 6’7” Draymond Green. When the game is on the line, Boston usually goes with 6’10” Al Horford in the middle. Size is still valuable, but today’s great giants are also quick and can knock down a 3 like Joel Embiid or Karl-Anthony Towns.

NBA post ups are endangered; the once-essential ability to both score and defend around the hoop has been replaced by positional versatility on defense and shooting and passing on offense. Those that can’t take their game to the perimeter are getting pushed aside in favor of a new breed of NBA centers.